Background: Image of human epithelial cells from the set from which the variation in the shape of EGFR was derived

Foreground: Model of human EGFR showing the new conformation lying flat on the membrane and the previously known upright conformation

A breakthrough in understanding a biological process that causes many common cancers including lung and breast cancer opens up a whole new realm of possibilities for the development of improved cancer drugs. The results are featured on the front cover of the journal Molecular and Cellular Biology (link opens in a new window) published on 12 May 2011.

Experts from STFC's Central Laser Facility (CLF) and Computational Science and Engineering Department (CSED) have solved a puzzle that has confounded scientists for more than 30 years.

The researchers have discovered a previously unknown molecular shape which is partly responsible for transmitting the signals that instruct cells within the body when to grow and divide. It is the uncontrolled growth of cells that causes cancer to spread through the body. Until now, not enough was known about how these molecules, known as epidermal growth factor receptors (EGFRs), transmit messages in the development of cancer. This means drugs designed to stop them transmitting these cancer-inducing signals have also been limited in their effectiveness.

Project leader Dr Marisa Martin-Fernandez, a CLF scientist based at the Research Complex at Harwell (RCaH), says: "A number of drugs aim to limit EGFRs' role in spreading cancer but because human EGFRs haven't been well understood, the drugs are designed simply to block every signal they transmit. But the human body is good at compensating for losses of function so it finds ways of bypassing blocked receptors to allow cancerous cells to grow again. Unfortunately the current drugs therefore all too often only provide temporary remission.

"Our breakthrough will provide a better platform of knowledge on structure variation of EGFRs in vivo. Potentially this enables the pharmaceutical industry to develop drugs that target EGFRs' cancer-related functions more specifically but also allow the receptors to go on performing other tasks. This makes it less likely that the body will try to compensate for total loss of function."

Peter Parker is the Principal Investigator at King's College London on this work. Dr George Santis, also from King's College London, is a consultant in respiratory medicine and will help take this work forward.

Dr Santis said, "Translating knowledge derived from scientific research into successful clinical therapies is exemplified by EGFR and its dysregulation in cancer. The use of new biologicals that inhibit EGFR has proved transformational in managing solid tumours particularly lung cancer where conventional anti-cancer treatment reached a plateau. There is however still much we don't understand regarding EGFR and its role in malignancy; this breakthrough provides the foundation for novel ways to assess EGFR in cells and tissues that may lead to new insights on how to target EGFR to treat human cancers."

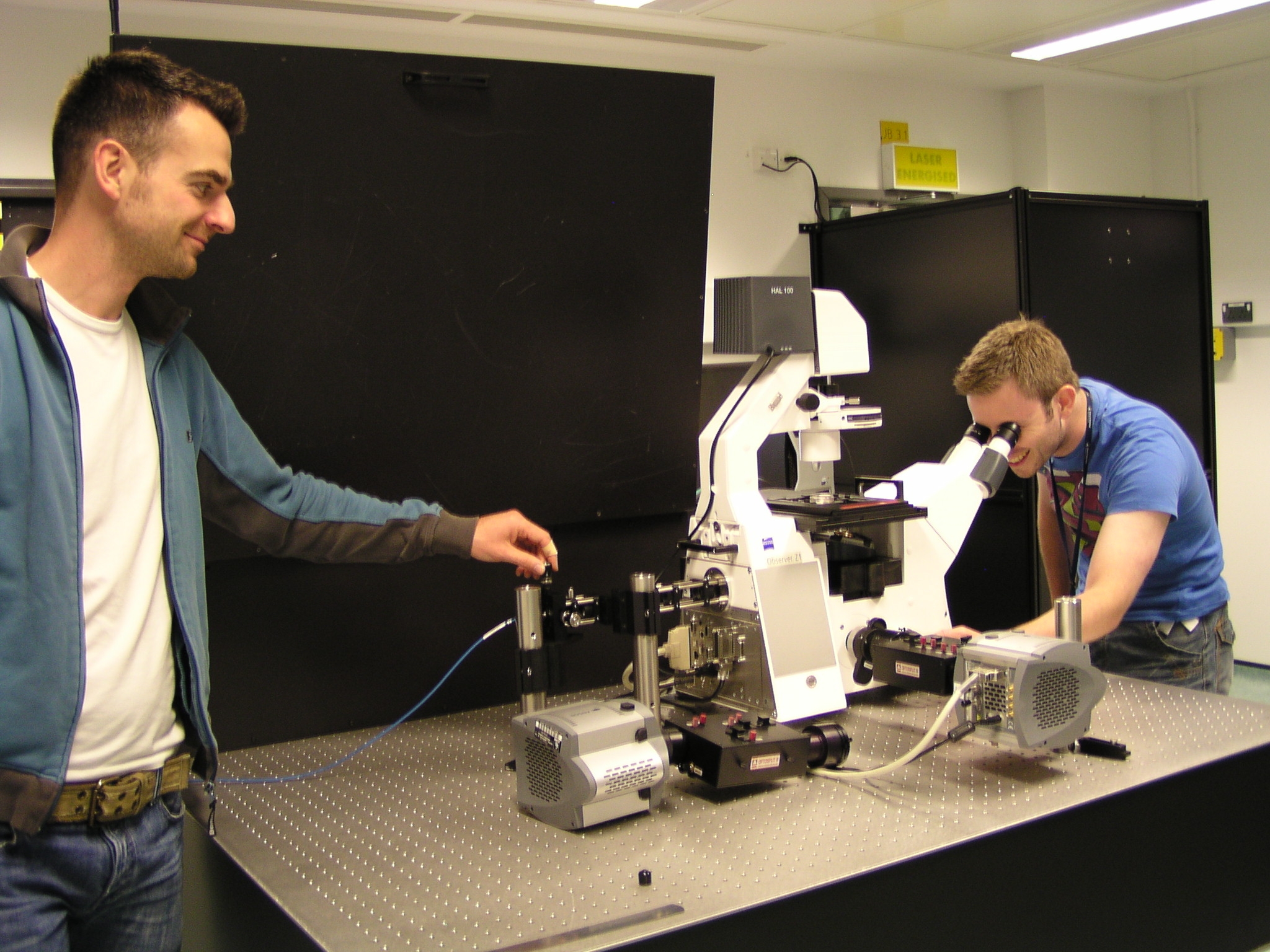

Aligning a microscope prior to experiments. On the right is Chris Tynan, one of the two lead authors of the paper published in Molecular and Cellular Biology; on the left is Stephen Webb, who is in charge of the single-molecule instrumentation in OCTOPUS

The team has also shown that this shape shares key features with the better understood EGFR molecules in fruit flies, providing clues on how EGFRs have changed during evolution.

Dr Martyn Winn of the CSED at STFC's Daresbury Laboratory says "The key has been close collaboration between the experimental and computational teams involved. The CLF used its OCTOPUS facility to take nanoscale measurements of EGFRs in cells. We took the measurements and used high performance computing (HPC) to calculate the receptors' high-resolution structure, allowing us to determine their similarities with the fruit fly EGFRs."

Professor John Collier, Director of the CLF, said, "Breakthroughs like this have the potential to really pay dividends in terms of saving lives and maximising the value of healthcare expenditure. By constantly pushing forward the boundaries of what laser technology can do, we can deliver real-world benefits that tangibly improve people's lives."

Details of the breakthrough are presented in the paper 'Human EGFR aligned on the plasma membrane adopts key features of Drosophila* EGFR asymmetry', and are featured on the front cover of the current edition of the journal Molecular and Cellular Biology published on 12 May 2011.

The work was carried out with funding from the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council (BBSRC) (link opens in a new window).